How Can We Help?

Are there COVID lessons to learn from the POLIO outbreaks of the 1950’s?

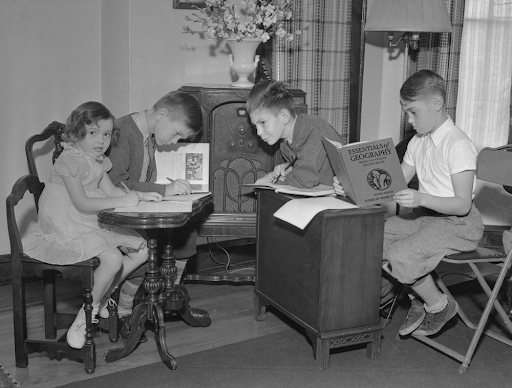

With so many photos over the last few weeks of smiling children in pajamas holding “My First Day of School” signs from their front door or living rooms, we have another set of memories for the COVID-19 time capsule – Fall 2020, when county by county, state by state, many schools chose not to reopen, and some did. While a recent Gallup poll shows a majority of parents don’t want their children back in classrooms full-time yet, the contortions in each home to facilitate remote learning for each child are tremendous and concerns that marginalized groups fall further behind are mounting. We find ourselves in complicated times.

A recent Time magazine article drew some interesting comparisons between the situation faced by parents today and that faced by parents during the polio outbreaks of the 1950’s. Polio struck communities seemingly at random. The United States had previously experienced outbreaks, but from the mid-1940s to mid-1950s, they came with relentless regularity. While the two diseases diverge significantly, the sense of powerlessness and unpredictability polio brought resonates in today’s COVID-19 pandemic, not least in the way outbreaks can affect the classroom. To read more, see Parents are facing tough choices about school in the COVID-19 Era. Here’s how people made the same decisions when it came to polio. Some highlights here:

- Mostly a summer illness, Polio often cropped up in the spring or lingered into fall, infringing upon the academic year—in San Antonio, Texas, an outbreak in the spring of 1946 closed schools at first for a couple of weeks and then for the remainder of the term, disrupting graduation festivities and prompting quarantines.

- Despite misunderstandings about how the virus was transmitted (mosquitoes and flies were incorrectly considered culprits), parents knew it was highly contagious, and spread when their children were in close contact with others. Social distancing—in the parlance of this pandemic—was the foremost countermeasure, even if it meant keeping kids cooped up when an outbreak abruptly halted summer fun.

- There was tremendous fear. Parents would give a “polio test” to their children every couple of days – can they touch their toes? Put their chin to their chest?

- It was a sickness harbored by silent carriers—the majority were asymptomatic, which scared parents. “Everything became a threat.”

- During the 1916 outbreak, New York City—which bore the brunt of the nation’s cases and deaths that year—shuttered schools based on rudimentary knowledge of how polio spread. When schools reopened and officials announced a policy of “leniency,” so many children were absent when classes resumed that there would often be only 2 or 3 children in a class of 30. In Minneapolis, a parents’ group lobbied successfully in favor of “playing safe” with additional delays, citing an enduring dilemma: “No one is absolutely sure of being right, one way or the other.”

- School closures elicited mixed reactions, with experts often disagreeing. Decisions were inherently unprovable because cases naturally fell when summer ended. Responses varied between localities, ranging from precautionary closures after one case to re-opening while polio lingered. The optimal level of acceptable risk was, as it is now, difficult to measure.

- When polio shut Chicago schools in 1937 during the Great Depression, it paralleled today’s concern that interruptions in learning could be devastating to students, and particularly those who were already the most disadvantaged. When educators experimented with radio lessons, the shift to at-home education magnified socioeconomic gaps—including disparities in access to technology.

The article concludes, “Polio was eventually defeated in the United States, thanks to vaccines administered to millions of schoolchildren in 1955. But the long journey to that point is a cautionary counterbalance to our impatience for a silver bullet to diminish the threat from COVID.” It goes on to state, “Perhaps the starkest truth the history of polio shows us is how little control we have in the face of a virus. Year after year, parents bore the anxiety of coping with an invisible threat to their children’s health, mitigating it as best they could within the constraints of their knowledge and foresight.”

Today, we look forward to a vaccine with cautious optimism, and stand in solidarity with all of the parents of today juggling work and their children’s remote learning, making decisions with limited information, and trying to do their best during challenging times.

Written by:

Jackie Phillips, MD, August 31, 2020

University of Southern California (USC) undergrad

Baylor College of Medicine

UCLA (residency)

UCLA (chief residency)